Developmental Epigenomics

The research in our lab aims to understand the contributions of the epigenome to embryonic development, cell differentiation and disease. We are particularly interested in how DNA methylation patterns are established, maintained and altered during those processes. Our interest in DNA methylation stems from the fact that this epigenetic mark can be stably propagated through cell division and that the presence or absence of DNA methylation correlates well with the activity of regulatory regions. Finally, a vast wealth of studies has demonstrated strong links between DNA methylation and various disease phenotypes suggestive of its potential applicability as a biomarker.

Research topics

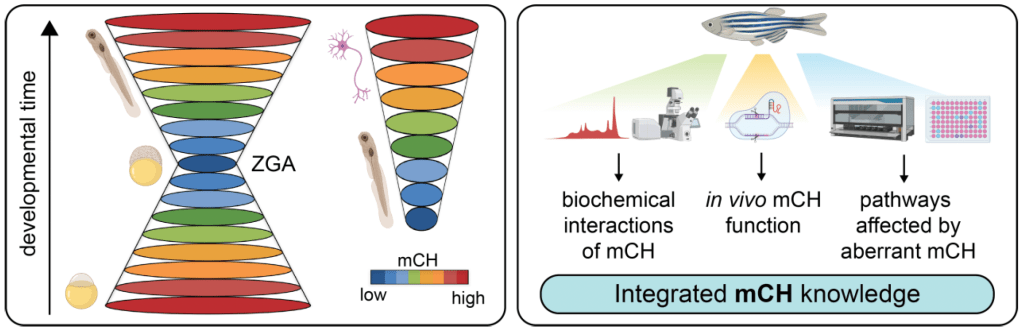

Atypical DNA methylation as a regulator of embryonic genome function

We have recently described embryonic reprogramming of non-canonical DNA methylation (mCH, where H = C, T, A) within mosaic satellite repeats (MOSAT), coincident with zygotic genome activation (Ross et al, 2020; Nuc Acids Res). Our CRISPR/Cas9 functional analyses in zebrafish larvae have unravelled Dnmt3ba as the primary MOSAT mCH methyltransferase enzyme. By using CRISPR/Cas9 and Cas13d genome editing technology in zebrafish, we are functionally interrogating the contribution of mCH and Dnmt3ba to embryogenesis, to better understand the developmental requirements for proper mCH patterning.

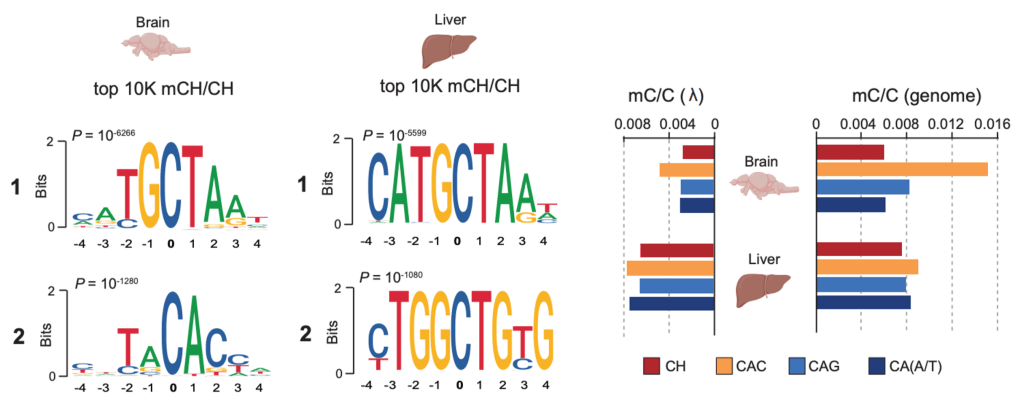

Dissecting the function of atypical DNA methylation “reading” and “writing” in vivo

We have previously shown that in zebrafish brains, non-CpG methylation (mCH), specifically mCAC, is enriched at distinct transposon motifs and in developmentally downregulated genes associated with neural and developmental functions. As in mammals, mCH progressively accumulates during post-embryonic brain development, a process dependent on the highly conserved role of Dnmt3a enzymes (Dnmt3aa and Dnmt3ab paralogs). Building on these findings, we are now generating zebrafish mutants deficient in mCH readers such as mecp2, as well as stable double Dnmt3aa/ab knockouts, which in zebrafish exhibit redundancy in maintaining mCG patterns. These unique genetic contexts enable us to selectively perturb mCH writing and reading without globally disrupting canonical DNA methylation. In combination with cutting-edge single-cell multi-omics and advanced microscopy approaches, these tools will allow us to dissect the contribution of mCH to neural development and to define the developmental requirements for proper mCH patterning in vivo.

Evolution of embryonic epigenome reprogramming

One of the most fascinating challenges in biology is understanding how a fertilized egg, which inherits highly specialized epigenomes from differentiated gametes, resets itself to give rise to the full diversity of cell types in an organism. To embark on this developmental journey, embryos must erase—or at least remodel—much of this “epigenetic memory” in order to establish a pluripotent configuration. In mammals, this reprogramming involves a near-global erasure of epigenetic marks, but our work and that of others has revealed that in teleost fish and cyclostomes this process is only partial, pointing to striking evolutionary differences in how pluripotency is achieved. We are now exploring how epigenomes are established during the earliest stages of embryogenesis across a range of vertebrate species, with the goal of uncovering both conserved principles and lineage-specific innovations. By comparing these strategies, we aim to gain fundamental insights into the molecular logic of developmental plasticity.